Certainties

alec vanderboom

The Little Engine that Had No Idea was chugging along on its track, happily entering a right-hand curve, its favorite kind. It did not see the rail that had been peeled back off the ties like a paper clip. It went roaring up and off, sun was seen briefly under its wheels, and then it careened headfirst down a ravine, taking trees and brush down as it went. When it finally hit bottom, it waited a long beat before gingerly testing itself to make sure it was still intact. It was afraid to find out, really. But it had absolutely no idea it was going to be derailed that day.

And so every big life change, mine included, can be described. It happens. Yeah, so what. Good news at last: It's beginning to bore even me, so this is the last official mention. See, I realize, s**t happens—devastating, horrific s**it oftentimes—to people in life. Even worse happens to the other animals; they endure it, we don’t notice it, since they don’t have blogs. Then we pick them up after they’ve been quieted in cool plastic-wrapped packages. But I digress. Thinking of pain always makes me take long scenic detours.

Two years have passed, and I sleep through the night. Big freaking deal—me and half the population, so there. Insouciance is wince-inducing when it’s a pose, but feels as great as fleece socks on a cold night when it’s real.

So I return to the site of the accident, a voyeur, to see what remains of the wreckage. I survey it from a cool distance, assessing what might be built out of it again, what working parts can be retooled and fitted into some other conveyance. At the time I dove nose-first into the ravine, I had worked for three years gathering information for a book on the ethics of dog training. The problem was, there came more and more information, an ever-towering growth of research that threatened to topple onto my head and knock me sprawling, and a seeming inability to ever master either the amount or the intricacies of it. So the big accident was a sort of blessing—bringing with it many other blessings, too, as I have recounted here—in that it temporarily derailed a project that had been heading down the wrong tracks. But the past week, as a result of certainties delivered either with a mean snarl, or a tossed-off ignorance posing as common knowledge, I’ve been thinking of that unwritten book again. Especially as those thought-provoking comments were uttered by men who likewise thought they knew something, but did not, about me. Their self-assurance made me realize I wanted no part of them, or anything they were selling. Another blessing.

One of the earliest ideas I had when I conceived of the topic was that a certain set of beliefs about dogs led to a certain mode of training them; let us call it the Republican method. Another way of conceiving of them led to a wholly different way of teaching, and that mindset might be termed the Democratic. Each side holds fiercely to its beliefs, indeed knows their way is the One True Way.

Certainly, I strive to incorporate “live and let live” into my daily routine, suffering idiots and wise men alike to teach me what they know, which is considerable in both cases. But the fact remains, there can only be a single truth when it comes to laws: evolution and intelligent design can’t coexist, notwithstanding the strenuous contortions of some religious scientists to make them do so; medieval belief in the Four Humors does not fit with what has been learned of the human body since the early nineteenth century; a flat earth does not behave as our globe actually does. And the human nature of the Republicans cannot be the same as the human nature of the Democrats.

One of these is right, and one of them is wrong.

One fellow, snarkishly dismissing the two grand I put out to the fence builders so that Nelly would not be ground into fur and tissue on the road we live on by the sixteen-wheelers that ply it, not to mention the overpowered four-by-fours of the local populace, informed me that an electronic fence would have been a better choice. When I femininely demurred, avoiding a fight by not voicing what I believe—They are cruel and stupid and the fact that no one would put a shock collar on their children is proof enough that they are not fit for dogs—but rather by saying, “I don’t really agree with those,” he snorted and laughed, “So you think it would hurt your dog?” Ha-ha. Well, obviously he knows better. Why, he wouldn’t even need to read this; he knows better just by osmosis.

He also knows what I need, apparently. Not what I want; what I should have. Him.

Another fellow, the next day, informed me from a lofty perch high above all canine scholars that dogs just want to please people, and also that one needs to be alpha dog to one’s pets. As the owner of some labs, and not a decidedly difficult little border collie mix who would probably be dead by now were it not for a lucky affection for food before all else, and thus amenable to thousands of applications of chicken jerky that have finally made her 80 percent reliable in most situations that do not involve rabbits (in which case all bets are off), he never really had to work with his dogs. He just thought he had. He practically sneered at me, paying Nelly from the treat bag for checking back in with me on an off-leash walk. He had no idea how hard-won, and how impossible to attain other than with repetition after repetition of reward, this behavior is—and how proud I am of both Nelly and me for getting there. He does not know, and does not care to know, that science has definitively put to rest the abysmal myth of dominance. This one dies particularly hard with those who do not wish to stop doing what they’ve always done, simply because they’ve always done it.

Just like assuming women like to be pawed, without being asked first.

Sigh.

Even if he (and by “he” I actually implicate many, including myself, when I smugly think I know everything—though that is usually the point at which the universe decides to gently instruct by swinging a two-by-four in the direction of my head) would step down off the stacked concrete blocks of certainty to educate himself, there is a dearth of scholarly work on the faint signals women send to suitors they are not interested in but lack the courage to say so to outright. Or maybe desperation—a similar train having wrecked in his own past—occludes the ability to read, either signals or the knowledge of anybody else.

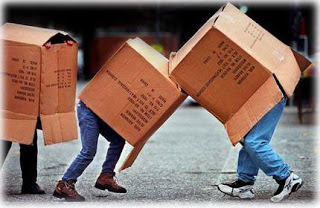

By this point in life, we are wheeling our broken and patched pasts around like filth-encrusted old shopping carts that have had too many hard meetings with parking lot curbs. Ba-ba-dump. Ba-ba-dump. On and on we go, the off-kilter wheel beginning to seem normal, the way it always was. Though once it spun free, chromed.

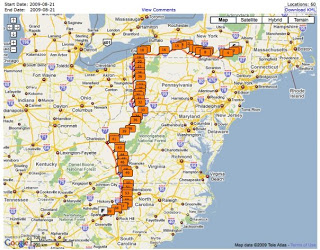

Whatever; icky though this brief passage has been, it has provided its own small gift, in my renewed interest in this paralyzed project. (I have life before derailment, BD, and AM, after motorcycles.) I’ve almost finished hoisting up those iron bits smashed against the forest floor, finished finding new use for them in the two-wheeler that’s taken me in a new direction, though it curiously feels also like an old one, back into life. I am going to spend some time figuring out, out loud, what it means to be here like this, at this particular time, with these particular people I’ve suddenly found myself in the midst of. Their extreme need to ride, if not mine.

Then I'll try to parse the difference between Democrats and Republicans, and give my dog some treats for doing the thing she is now certain is right.

I find I know less and less, like I am growing backwards with the years, into a fresh young creature, a baby ignorant as bliss.

I find I know less and less, like I am growing backwards with the years, into a fresh young creature, a baby ignorant as bliss.Nelly Prays (c) Andrew garn