See SPOT Run

alec vanderboom

The morning dawns—or not quite.

My first thought upon lifting the coffee cup to my lips, 4:30 a.m. on the 21st, the bike standing outside, shrouded in its cover and ready to go: Remind me why I am doing this?

It is, naturally, a fundamentally unanswerable question, like all the most essential ponderings about life. And not just the ones concerning riding. Suddenly it seems so pointless, just like many of my ideas when they come to the point of doing, as opposed to the point of conception. Ride a thousand miles in one shot?

The purpose—for the lark of doing it, that’s all—was to know a little whereof I hoped to speak. Google Maps graciously gave up the simple number, the mileage to

Some things you just have to see for yourself.

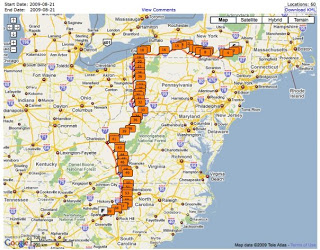

With the addition of a couple hundred more miles, I could find out for myself what it felt like, this racking up of numbers for their own sake. I could find out if I was capable. I had no idea, but I was going to try for my first Saddlesore 1000, an Iron Butt Association certified ride. I would do so under the tutelage of an IBA master, who offered his signature on my initial witness form, and myriad other bits of invaluable information, as well as a SPOT tracker to memorialize the event; no one else would care, but one must have a SPOT track these days, apparently. He would stay behind me all the way, permitting me the semblance of my own ride. And more than a semblance of my own mistakes.

My hoped-for 9 p.m. bedtime somehow turned into 11:30 p.m. (and it was not just fault of last-minute preparation of the two peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches that, together with the six bottles of water already tidily asleep in the topcase, would form the cornerstone of the next day’s sustenance). Then it was hard to sleep. And then it was hard to stay asleep.

The sun rose as we went west, into what felt like beautiful adventure. It always feels like beautiful adventure when you’re only an hour into the ride.

That was the thing: we were going west, in order to go south. We were going west to add miles, not to go anywhere in particular. This knowledge, this

The majority of motorcyclists do not get this; some are adamant in their belief that this is not motorcycling, as they understand it. Motorcycling is about travel. It is about hitting the turn signal when the urge strikes, lying in the grass by the wayside, being taken by serendipity, and taken in by alluring signage. About stopping as much about going. But as I was throttling down the highway, it hit me: Long distance riders do see things along the way; they just do it faster.

Indeed, I was seeing things: after six hundred miles, I was either seeing a state border sign, or I was imagining it. Where the hell was I now, Virginia or

It turns out I was going too fast, which was tiring me, which made me anxious, which made my muscles ache, which caused me to take too long to stretch out at the gas stops, which then made me feel like I had to go fast once I got on the slab again.

I felt the imperative now to go, to go. My bike and I were pressed by time and desire into one item, and we needed something. I was getting it.

The miles continued to fly past. My mentor was keeping track, in a way I was unaccustomed to thinking, along lines of pure consumption. “Only two more stops,” or “This is number 5,” he would say, so I could note the stop number and the odometer reading on the back of the gas receipt, sparing me the more picturesque method I had originally conceived of, or a few minutes of searching through the previous receipts because of my inevitable inability to remember my own past, immediate or not. If not for him, and the IBA’s raison d’etre in record-keeping as crucial partner to experience, I would have been laboriously notating things (and thus attenuating effort) in a small black loose-leaf binder that had belonged to my father and for which I had previously never found other use. I wonder what he would have thought of his daughter out here on the highway; no, I know. Bemusement. And acceptance. Just as he accepted all the permutations of human endeavor, especially the most extreme and therefore the most pointless of all.

Was this the purpose of the rainbow that, around one corner, now banded the sky and made one end the goal of the road’s vanishing point? Oh, sure. Saddlesore; pot of gold: same thing.

The state lines were passing; not exactly flashing by, but here comes

The last 80 miles were the ones I did not think I could make. Probably because I knew there were only 80 miles left to go, and I would not, could not stop now. I blinked my eyes quickly; I felt angry at the traffic this late at night. It did not seem fair to impose tailgaters on someone who was just trying to get somewhere, and stay awake doing so.

Then, suddenly,

I got to bed at 1:42 a.m., after nearly twenty hours awake. The next morning, watching at the meticulous multi-step tech inspection of these greatly modified machines, with their fuel cells, dual GPS, hydration systems, and shipboard packing layouts, I realized the smallness of what I had done, and the enormousness of what they were about to launch themselves into. For the next two days, the intensive preparations continued, as they had for each of these hundred riders for the months and even years before. The Big Dance was nigh. The quiet motorcycles radiated an energy of anticipation, it seemed. And finally, at ten a.m. on Monday, the signal was given, a hundred engines cranked, and something caught hold of my throat. I was held motionless as one by one they were taken by motion: in a precise ballet, each one at thirty-second intervals cut a smooth, sharp turn out of the parking lot. The riders waved, and the air filled with the sound of their horns’ final farewell. In minutes they were gone. What they left behind was a memory, heavy as air, of their having been there.

Now I am haunted. I keep thinking of them still out there, running the roads of