Predation Picnic

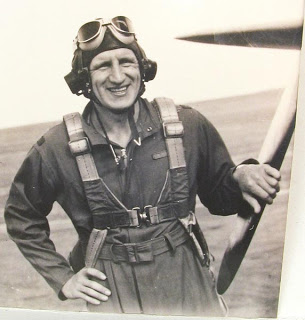

alec vanderboom

Some days build into magic, and you can never know which days those will be when you set out. Remember this. I had forgotten to remember, when I showed up for an afternoon art exhibit in the nearby burg of Rosendale. A small canal town enlivened at the end of the nineteenth century by the cement industry (Rosendale cement was famed, and ended up in the pilings of the even more famed Brooklyn Bridge), it has now been re-colonized, a century later, by a new generation of Brooklynites. These are the hipsters looking even farther afield than the shores of the tapped-out borough that is simply too cool for most humans: it will slay you dead if you dare to show yourself in Red Hook without the proper accoutrements. The shame of it! I call Rosendale "Williamsburg North."

On this Saturday afternoon, the Interesting people had gathered in the town park for a show of sculpture and furniture made sensuously from cement, on the site of derelict kilns cut out of natural caves in the cliffs and then bricked in. A little grassy sliver of park with some big rocks and little running water, which is all children need to amuse themselves with for hours, so the grown-ups can conduct their business (which my son defines as "yak-yak-yakking for hours!"), aided by microbrew from a keg. Of course, since events in Rosendale are always louche and cool--ruleless--off-leash dogs wandered among the yakkers. As did a couple of twentysomethings who were got up in costume they had taken from the set of Gangs of New York. Nelly, though, was ordered to stay on leash, at least until the giant platters of cheese and Asian noodle salad were all gone. Not even Rosendalians will suffer a dog to stand in their food and gorge on it till sick.

Lots of friends, no goddamn computers, a pretty day: magic rose up out of the grass. The children were up to their knees in pond scum, and so it was magic for them, too. Four hours, and nary a toy, just opportunism: using empty beer cups and gravel from the parking lot, they built dams in the stream, and jumped from rock to rock. With all the cheese finally gone, it was time for Nelly to groove the day as well. I dropped her leash.

That was the moment I apparently forgot where I was. Rosendale. Rosendale--where there are chickens on leashes.

It happened so fast you could practically smell the release of adrenaline into the air. Nelly and chicken, different sorts of extreme desperation acting as rocket fuel (life and death, respectively). Around in a circle of increasing velocity, and I tried to grab the ring on this infernal carousel. I have rarely acted this fast. In a blur.

How glad was I she was still wearing her leash? Well, how glad is the chicken to be alive still? Just before the first mouthful of feathers, I glimpsed an opening. It was worth the skinned knuckles: I got her. Magic. Friends who had observed from far off came over to commend the mindless burst, the save. Nelly was shaking. Every cell in her body was on high alert. She wanted chicken dinner. Warm chicken dinner.

The day, and its happy vibe, was preserved. We went home to eat our dinner of omelet. I let Nelly lick the pan. That is as close as she was going to get that day--the skin of her teeth. I was so glad I had not let her out of the house that morning, because there was a newborn fawn in the side yard. Alive, and magic.

The day, and its happy vibe, was preserved. We went home to eat our dinner of omelet. I let Nelly lick the pan. That is as close as she was going to get that day--the skin of her teeth. I was so glad I had not let her out of the house that morning, because there was a newborn fawn in the side yard. Alive, and magic.

On this Saturday afternoon, the Interesting people had gathered in the town park for a show of sculpture and furniture made sensuously from cement, on the site of derelict kilns cut out of natural caves in the cliffs and then bricked in. A little grassy sliver of park with some big rocks and little running water, which is all children need to amuse themselves with for hours, so the grown-ups can conduct their business (which my son defines as "yak-yak-yakking for hours!"), aided by microbrew from a keg. Of course, since events in Rosendale are always louche and cool--ruleless--off-leash dogs wandered among the yakkers. As did a couple of twentysomethings who were got up in costume they had taken from the set of Gangs of New York. Nelly, though, was ordered to stay on leash, at least until the giant platters of cheese and Asian noodle salad were all gone. Not even Rosendalians will suffer a dog to stand in their food and gorge on it till sick.

Lots of friends, no goddamn computers, a pretty day: magic rose up out of the grass. The children were up to their knees in pond scum, and so it was magic for them, too. Four hours, and nary a toy, just opportunism: using empty beer cups and gravel from the parking lot, they built dams in the stream, and jumped from rock to rock. With all the cheese finally gone, it was time for Nelly to groove the day as well. I dropped her leash.

That was the moment I apparently forgot where I was. Rosendale. Rosendale--where there are chickens on leashes.

It happened so fast you could practically smell the release of adrenaline into the air. Nelly and chicken, different sorts of extreme desperation acting as rocket fuel (life and death, respectively). Around in a circle of increasing velocity, and I tried to grab the ring on this infernal carousel. I have rarely acted this fast. In a blur.

How glad was I she was still wearing her leash? Well, how glad is the chicken to be alive still? Just before the first mouthful of feathers, I glimpsed an opening. It was worth the skinned knuckles: I got her. Magic. Friends who had observed from far off came over to commend the mindless burst, the save. Nelly was shaking. Every cell in her body was on high alert. She wanted chicken dinner. Warm chicken dinner.

The day, and its happy vibe, was preserved. We went home to eat our dinner of omelet. I let Nelly lick the pan. That is as close as she was going to get that day--the skin of her teeth. I was so glad I had not let her out of the house that morning, because there was a newborn fawn in the side yard. Alive, and magic.

The day, and its happy vibe, was preserved. We went home to eat our dinner of omelet. I let Nelly lick the pan. That is as close as she was going to get that day--the skin of her teeth. I was so glad I had not let her out of the house that morning, because there was a newborn fawn in the side yard. Alive, and magic.