Wild and Crazy

alec vanderboom

Last week, we celebrated Endangered Species Day. (Or you know what I mean: not

a whole lot of celebrating going on.) In its honor, I wrote about

a new book that is both important and a masterpiece of absurdism--an amazing

feat perhaps only attainable when confronting the subject of man's

relationship to the rest of creation.

Here's my review, which appeared in slightly different form in The Daily Beast.

Appropriately enough.

Happy Endangered Species Day! Well, “happy” might not be the word, since there are

currently over 1,200 species of fauna listed as endangered or threatened, and

those are only the ones we know about.

Some as yet undiscovered may well have disappeared between the time we

lit the birthday candles and, appropriately, blew them out.

If

you’re in the mood for a celebration anyway, the Endangered Species Coalition

suggests you consider visiting a wildlife refuge, help prevent the deaths of

millions of birds each year from colliding with windows by affixing decals to

yours, slow down while driving to avoid turning the berm into any more of a

wildlife cemetery than it already is, or stop dousing your lawn with chemicals. You could also depress the heck out of

yourself by watching the 2010 documentary Call of Life, in

which eminent scientists posit the probably inescapable mass extinction of over

half of all plant and animal species before the end of the century. My recommendation, though, is to read Wild Ones: A Sometimes Dismaying, Weirdly

Reassuring Story About Looking at People Looking at Animals in America, Jon

Mooallem’s stupefying account of our historic inability to stop meddling with

everything under the sun—bringing masses of creatures to the brink of

extinction, then expending perverse amounts of energy and ingenuity to haul

them back, one by one. “Dismaying”

is right, “reassuring” sounds like it came from the marketing department, while

“brilliant in conception and execution” doesn’t fit on the cover but should.

The

author, a writer for The New York Times

Magazine, gives only a brief history of the act signed into law forty years

ago (“Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich

array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” opined President

Nixon, pen poised), because his main subject is instead the bizarre gymnastics

we have sometimes performed to uphold it.

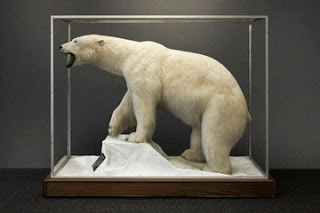

He uses three examples—the polar bear, Lange’s metalmark butterfly,

whooping cranes—to explore our confounding and contradictory relationship to

the brethren species with whom we share the planet, though apparently we share

the way toddlers do with sandbox toys.

All three of these endangered species are charismatic—awing us with the

kind of aesthetic endowments lacking in the Helotes mold beetle, say, or atyid

shrimp (“off-brand animals,” in the author’s sly term)—and so they call forth

our most conflicted response, the better for Mooalem to display and dissect.

When

first encountered the animals of the New World were so profuse we could not

imagine them otherwise, although we wanted to; wolves, bears, and cougars were

the massed enemy on the hill, and our stories were of their unbridled

ferocity. Only when we had finally

(ferociously) cracked some links in the Great Chain of Being that Thomas

Jefferson, for one, had believed could never break—“no instance can be produced

of [nature] having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct,” he

declared—did the morals reverse.

As soon as the grizzly bear “disappeared from the land, it found new

prestige in our imaginations,” Mooalem writes, and his book is truly about the

animals of our imaginations, because it is their status there that will lead us

either to eradicate them or to save them (or both at the same time; since 2007,

eleven whooping cranes—of a population of fewer than three hundred laboriously

nursed into existence from the small handful left alive in the 1940s—have been

found shot, and in 2011 a Minnesota farmer smashed thousands of eggs and young

chicks of the federally protected American white pelican).

As

a carnivore that naturally ranges over vast territory, the polar bear does poorly

in captivity, developing stereotypies (think Gus “the Bipolar Bear” of the

Central Park Zoo, ceaselessly swimming the same circuit of his small

pool). Now they’re doing poorly in

the wild too, dropping from starvation as the ice from which they hunt forms

later and melts earlier due to climate change. This is why the town of Churchill, Manitoba, on the Hudson

Bay (which a conservationist estimates will stop freezing entirely by 2050,

dooming one of only nineteen polar bear populations on the planet), has become

a favorite stop on the “Last Chance Tourism” train. Mooalem visits at the same time Martha Stewart does,

although she proves more elusive than any of the bears. It is one act in the theater of the

absurd Wild Ones presents in all its

prodigious eccentricity, but by no means the most outrageous. It is hard to say which of the

increasingly nutty episodes in man’s tortured relationship to his own

conception of wildness here is the most outlandish: page by page they

mount. You can only stand back and

gape. (Only rarely do the animals

have the last laugh, as do three and a half million Canada geese today: in 1962

only a single flock could be found, which was prayerfully coddled and fed,

raised and reintroduced. So they

could later be shot, gassed, eggs scrambled in-shell, and chased away by eager

border collies.)

Butterflies,

the stuff of so many glitter stickers and ankle tattoos, are nature’s airborne

art. They seem to capture a sense

of ephemeral life at its most impossibly beautiful, so our sadness at the

prospect of losing even one of the approximately 20,000 species of butterflies

known to exist is understandable.

What is not is the contortions a few governmentally supported

conservationists (along with a host of concerned, or obsessed, volunteers) must

execute to preserve a tiny remnant of Lange’s metalmarks in the small,

grotesquely compromised habitat of the 67-acre (55, says the government

website) Antioch Dunes National Wildlife Refuge. The sand dunes were relentlessly mined in the past century,

and a gypsum plant and power lines split the park. In 2006, only 45 of the orange-and-black butterflies could

be found, down from thousands a decade before. They lay their eggs only on naked stem buckwheat, which is

being overrun by invasive hairy vetch that has to be pulled out by hand or

herbicided to death (with predictable fallout, namely the harming of butterfly

eggs). The attempts to maintain a

viable habitat this isolated—attempts, dubbed conservation reliance, that are

at once comedic and tragic, a strange opposition balletically explored

here—illustrate the phenomenon of “island biogeography.” As David Quammen

described in his elegiac Song of the Dodo,

islands are “where species go to die.”

But as Wild Ones shows,

they’re not going down without a fight—even if it is a futile one, and involves

lots of grad students with plastic cups and captive female butterflies.

When

finally we read of whooping cranes reared by humans in costume, taught to

migrate behind men in ultralights, and shoved away from food sources deemed

insufficiently wild, the question can no longer be avoided: For whom do we do

this? Probably not for the bird

who has just been pepper-sprayed “to promote wildness.” Such efforts—“heroism in the Sisyphean

sense”—seem to be made primarily for us, so we can write a bedtime story that

contains man and animal intertwined, exchanging nobilities.

This

book is dense with both thought and fact, but no one will mistake it for an

article in the journal Biodiversity. It is written with a vernacularly light

touch, shot through with compassion and wit, not to mention open amazement, the

only apt response to the story of our monumental hubris.

Zoom out and what you see is one

species—us—struggling to keep all others in their appropriate places, or at

least in the places we’ve sometimes arbitrarily decided they ought to

stay. In some places we want cows

but not bison, or mule deer but not coyotes, or cars but not elk. Or sheep but not elk. Or bighorn sheep but not aoudad sheep. Or else we’d like wolves and cows in

the same place. Or natural gas tankers swimming

harmoniously with whales. We are

everywhere in the wilderness with white gloves on, directing traffic.

At

the end of this rich feast of irony, let there be cake. Make a big wish, America. Then blow.