Last summer--how can it already be that long ago?--I traveled to the National.

What's "the National"? And of what nation do we speak?

Read on.

This is the unexpurgated version of a piece that appeared in Motorcyclist magazine.

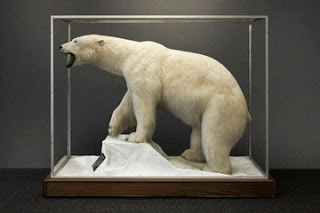

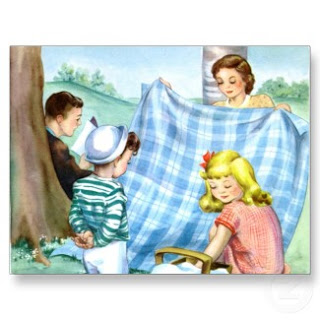

And these are two of my favorite photos taken by my pal Joe Sokohl; used here by kind permission.

Now, excuse me while I go pack to go to another rally.

I am in

northern Pennsylvania on one of the oldest

highways in America,

the transcontinental U.S. 6, doing what I love best: eating a luggage-smashed

peanut butter and jelly while sitting on the curb at a gas station in the

company of the vehicle that brought me here.

I am scribbling in a notebook a few of the six hundred - odd thoughts

that occurred to me during the past 140 miles (tank limit), and also on why I

seem compelled to do this mainly when I sit on a curb, looking at my

motorcycle. Through it also; air is its

heart. A bike is both solid and

insubstantial. I write that down too, as it occurs to me it’s a good metaphor

for pretty much everything.

And it

makes strange sense, because I am making for a gathering that is simultaneously

as unlikely as chance can make anything, and as absolute as familial blood: the

41st annual national rally of those who ride the motorcycle

conceived in 1920 by three World War I veterans of Italy’s Corpo Aeronautico

Militaire and built in a village perched on the rocky shore of Lake Como. Then there is the fact that we are meeting

to pledge allegiance to our small-town Moto Guzzis in a village in the Virginia foothills of the Shenandoah, Buena

Vista. If that isn’t a

little weird, I don’t know what is.

Guzzisti

are themselves a peculiar lot—a bit like the air-cooled V-twin itself, maybe,

an engine about as refined as a tractor’s but curiously gorgeous too—and in the

decades I have known them I have compiled the riders’ Identi-Kit: in descending

order, their livelihoods are most likely to be engineer, IT, photographer,

pilot, musician, and academic. They are

“independent thinkers,” and they are a veritable portrait of middle-class America (with

the exception of Billy Joel). An owner

of one of Mandello del Lario’s output is most likely to retorque his own bolts,

possibly wearing a tee that reads “Moto Guzzi: Going Out of Business Since

1921.”

I know

motorcyclists who have never been to a rally, but I don’t understand them. A rally is a combination community barbecue,

mutual need society, and tent revival. A rally on the calendar is the

motorcyclist’s ritual call to prayer, his

muezzin. From May through September,

hundreds of regional rallies convene various tribes, which will each attract a

couple hundred; it is the nationals that are the big deal. BMW’s is an industrial-scale shindig with

hundreds of vendors and a full docket of seminars and tours for its 10,000

attendees. For Moto Guzzi, which is

lucky to sell 600 production units a year in the U.S., four hundred diehards will

converge. This year the factory will

send neither demo bikes nor even a representative, perhaps in memory of 2007’s

disastrous rally in Houston,

Minnesota: a flash flood swept

away their entire fleet not to mention the semi they came on, along with much

else. A rally is the usual ride, writ

large: Four days and hundreds of miles; four nights of beer, bourbon, mediocre

potato salad, campfires and campfire tales; four hundred buddies, not

four. We will meet whatever comes—pain

or pleasure, or usually both—together.

The banner hung from the park pavilion’s rafters proclaims a truth. Moto

Guzzi: A World of Friends.

On the

first day of two I need to get there, I choose the back roads that my bike—a

1986 650cc Lario—prefers over “the slab,” the anonymous interstate that gets

you somewhere without letting you know just how. I am traveling old-school, with tent and

sleeping bag strapped to the seat, paper maps, and a route cribsheet in the

vinyl map pocket of my tankbag to read while riding and therefore invariably

misread. I had to make a guess at the

junction of I-180: lo, it does not in fact run north-south as it does in my

road atlas. OK, then, West. I had a fifty-fifty chance of being

right. I have never won the lottery,

either.

But I chose

right, in a way, the way of the journey.

On the phone to friends waiting that evening for me at a Comfort Inn in Maryland, I report the

good news: I have discovered an amazing road in Pennsyltucky (as it is called, presaging

the next day’s dive into the real South).

Route 74 from Port Royal to Carlisle

exceeds every criterion of goodness the motorcyclist asks—little traffic,

uncountable curves, scenic surprise.

Then there is the bad news: I had to go a hundred miles out of my way to

find it. No matter. As a famous long-distance rider I know says,

“There is no such thing as a bad day on a motorcycle.” I would eat a grocery-store meal in the room

when I got there, after the rest had returned from their pub dinner. For some reason, my notion of what

constitutes excellent grub reverses itself on a motorcycle trip.

The good

day/bad day switch occurred to Tom from Massachusetts

the next day. We were finally on the Blue Ridge Parkway, the legendary road

that always inspires a prayer to dual gods: the one in charge of providing an

asphalt dancing partner who never steps on your toes and can seemingly waltz

all night, and the one who permitted us to safely wade into socialist waters

long enough for the WPA to build an unprecedented temporal museum of culture

and geography the length of a road. Tom

dropped out of sight in our rearview mirrors, and when we doubled back to find

him at a scenic overlook, he announced that the main seal on his lovingly

restored 1973 Eldorado had given way.

It’s not a Moto Guzzi event without leakage.

It is also

not a Guzzi event without the selflessness of the brotherhood’s bond becoming

manifest. Tom got on the phone to a fellow sixty miles away who immediately

agreed to come with a truck; once at the rally, the Eldo traded places on

another rallygoer’s trailer with his Norge (named after the Guzzi that in 1928

accomplished 4,000 km to the Arctic Circle).

Tom would head home at the end of the weekend on a fully functional

late-model machine, a kindness extended simply because both men had, one day,

found the same object of an outwardly inscrutable affection.

As we

pulled in to the rally grounds at Glen Maury Park, my long anticipation of

arrival—and to me, a rally is as much about expectation as it is about being

there—insured that all I could see were the tents massed along the treeline,

the people moving back and forth between their sites and the bathrooms, the

pavilion like Valhalla on the hill ahead, bikes passing us on the drive as they

headed for ice, or for a ride on the fabled roads of Virginia. Who might I meet again, after years that

would seem as moments? It was only later, after I had unpacked and furled the

tent, that I even noticed the park was dominated by Paxton House, an imposing antebellum

mansion. This gathering, from all

corners of a united republic, of fans of a European motorcycle few have heard

of would be overseen by the ghost of a Confederate general.

In his

honor, perhaps, or maybe just because they’re tasty, that night we enjoyed mint

juleps by the light of tentside tiki torches.

In honor of no one but global warming, the next day we sought refuge

from the excoriating heat (102 and counting) in a pool below Panther Falls,

attained by carefully negotiating three miles of steep downhill gravel

road. And that night, all hell broke

loose.

After

dinner, the time of commingling and chat, beer drinking and good-natured

complaint, someone walked over, smartphone in hand. “Folks, there’s a big storm headed our

way. About fifteen minutes.” The radar showed a dense green mass, admixed

with angry yellow and orange, stretching from southern Ohio

to Tennessee

and moving east. Within ten minutes,

rallygoers had assisted everyone in battening down tents and bringing bikes

under the pavilion’s roof. Then we

waited for the show to begin. Some

thoughtful person had left a box of Cheezits on a table, which we devoured

while watching lightning shear the night sky and trees bend under the force of

brutal winds. The storm was a derecho, and when it had passed, it was revealed

as one of the most destructive storms in American history. We had felt strangely calm. Everything was going to be all right, or

would be made so later. Guzzi people are

good at fixing things.

The next

day brought departure. A friend

familiar with local roads saw me on my way by leading a private tour, and that

is when we saw the storm’s full aftermath: great trees snapped in half, wires

festooning pavement. He found what was

certainly the state’s only craft brewery with enough generator to power both

air-conditioner and pizza oven.

Afterward I said goodbye. I was

headed north, home, alone.

But a

motorcyclist knows this is not how it will always be: alone. Next year we will

be rally-bound again. There will be new

expectation. New affiliations. And a new date on the calendar on which to

fix an anticipatory pin, every year.

When we come together, and when we arrive.

{Photos: Joe Sokohl}