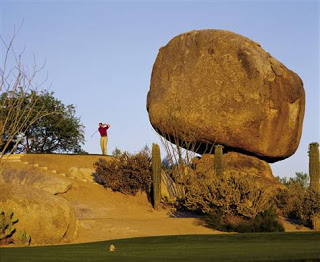

Golfing in the Desert

alec vanderboom

The earth owns itself.

The earth owns itself.What a strange concept, eh? It's very similar to the notion that An animal owns itself (the idea that PETA tries, in its regrettably bullheaded way, to get across--and an idea that is so logically, morally, and intellectually unimpeachable that the greatest difficulty I have now in life may well be trying to wrap my brain around how a single human, much less most of us, can hold beliefs like "animals are ours to wear" or "animals are ours to torture to death with chemicals" or "animals are ours to cage so we can look at them").

Add now to the list, though a bit farther down in immediacy, the difficulty in comprehending what's up with building golf courses, not to mention spas, luxury condos, and vast retirement communities, in the desert.

That bizarre concept--the voiceless earth has a right to speak--came into my mind as I was driving north in the Arizona desert recently (yes, in a car, with my closest relatives in it with me, only weeks after I had been in Arizona on a motorcycle, gloriously free of the compunction to order a Bellini at poolside). We were driving back to lie down and nurse the aftereffects of a grand dinner that included a bottle of champagne, and lobster--the latter not ordered by me, I'll have you know, since I also have a tough time getting the logic of putting a living creature into boiling water. It was the most lavish meal I'd had in years, in honor of my mother's eightieth birthday, and we were en route to the most lavish resort I've ever been in, an almost sickening spread of lush villas and a spa and, of course, the grotesque indulgence of golf greens made to grow from desert sand amid the saguaros.

Yet there are javelinas out there still, in the night . . .

(I longed to see one, but restrained myself from leaving tortilla chips out on the back patio so I might have a sighting. A fed wild animal is a dead wild animal. And I'm really, really sorry for feeding that chipmunk at the Grand Canyon, but he raised his hands in supplication and told me he was starving. Truly.)

"Someone bought this land, when it was boulders and space," my sister wonderingly said.

"Bought it from whom? Who 'owned' it?" I asked. Stolen from the Indians, who never dreamed of a thing called ownership. Strange concept, made up from whole cloth, I am beginning to suspect.

And that's when I thought it. The earth owns itself already, so it can't be owned by us. How then did the idea get flipped over on its back, so now it waves its four legs helplessly, scrabbling at the air? "We own it all." So that it, like all our animal brethren in the world, can be bought, sold, killed, or played golf upon.

Strange concepts indeed. I'm taking an aspirin and going to bed.