The Bad Seed

alec vanderboom

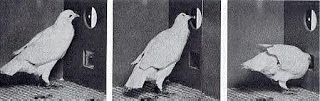

B. F. Skinner, who was an English major before he was a psychologist, came up with the lovely term "superstitious learning" for a phenomenon he witnessed when working with pigeons. It is something all higher animals, including ourselves, are prone to:*

The bird behaves as if there were a causal relation between its behavior and the presentation of food, although such a relation is lacking. There are many analogies in human behavior. Rituals for changing one’s luck at cards are good examples. A few accidental connections between a ritual and favorable consequences suffice to set up and maintain the behavior in spite of many unreinforced instances. The bowler who has released a ball down the alley but continues to behave as if he were controlling it by twisting and turning his arm and shoulder is another case in point. These behaviors have, of course, no real effect upon one’s luck or upon a ball half way down an alley, just as in the present case the food would appear as often if the pigeon did nothing–-or, more strictly speaking, did something else.

I wonder if there are even closer examples to Skinner's original, with humans and food. (One from my own life concerns a certain borscht made by a college roommate; I had some just prior to a virulent flu making its appearance and laying me low. To this day, the sight of a beet makes me want to puke.)

There are evil demons abroad. They shape-shift: they visit us in their earthly form as allergies. I don't mean the kind of allergies that send one to the hospital with hives, gasping for breath. I mean the ones we decide are allergies. I mean the superstitious ones.

An early classmate of my son was known as allergic to dairy. It's pretty amazing how much of our food contains milk or butter; this little girl was carefully guarded from all of it. Her teeth had turned brown, but she was otherwise safe. At a birthday party once I was seated next to the mother. Curious, I asked how the allergy had first manifested itself in her daughter. She related how, when her baby was first given solid food--cereal mixed with milk--she developed terrible constipation.

You mean that was it? I wanted to say (but didn't). Because I instantly recalled the constipation that had made my own baby cry after he first ate solid food. In the kind of panic only a new mother can feel--and did, on a daily basis--I raced him again to the doctor. "What can be done for him?" I breathlessly demanded. "Have you ever heard of . . . . prunes?" he asked as if he were talking to a moron. Which he was.

It is not possible for me to count the number of people I know who have gone off wheat. Perhaps many of them suffer from celiac disease. Perhaps many of them do not. All of them report that they feel "better."

We are searching. For safety in a world that, for all its fences and airbags and margins, still feels unsafe. Because we are going to leave it at last. We are right to be frightened, somewhat, of the water, the air, the poisons that seep in and around. But if we can give a name to just one, drawn a cordon around it and banish it forever, we may control all the dangers by proxy. It is superstitious, but it is understandable.

I too want to be washed clean of sin, reborn. But evil hides, swirling in vaporous ether all around. It has no corporeal form; I cannot see it in order to expunge it. Maybe the toast will have to be sacrificed instead. I drive a bullet through its glutenous heart. I feel better already.

*One example, from the dog world, is an unfortunate one: Say a dog is wearing an e-collar because he is enclosed by an invisible fence. He comes too close, gets zapped, just at the moment a child goes by on a bicycle. He imputes a causal relation to the two events, even though there is none. One only has to imagine what might happen the next time a kid on a bike visits the household.