Deeper

alec vanderboom

Lately I have been given to recalling how I lived not in this world but in profoundly sensed others a long time ago. The reason I now remember is that boy out there, visible through the verticality of bare trees in the woods. He is slashing his invisible enemies with swords that are transformed from sticks to glinting metal, indomitable in his hand alone. He is not playing; he is truly there, in the unearthly din of battle (only supplemented with those shkk-shkk sounds from his mouth), loacating himself at the extreme edge where death and heroism meet. Childhood fantasy is big. It is as big as Wagner and Beethoven and Jackson Pollock put together. It is not made of small things; it is the biggest thing there is. It is the only thing.

Lately I have been given to recalling how I lived not in this world but in profoundly sensed others a long time ago. The reason I now remember is that boy out there, visible through the verticality of bare trees in the woods. He is slashing his invisible enemies with swords that are transformed from sticks to glinting metal, indomitable in his hand alone. He is not playing; he is truly there, in the unearthly din of battle (only supplemented with those shkk-shkk sounds from his mouth), loacating himself at the extreme edge where death and heroism meet. Childhood fantasy is big. It is as big as Wagner and Beethoven and Jackson Pollock put together. It is not made of small things; it is the biggest thing there is. It is the only thing.Psychologists tell us it is the way we arrive at theories, in the safety of our tender youth, of how we are to exist in this strange community of others. Fantasy is formed of pure logic, but painted with colors so vibrant they would hurt the eyes of adults. And the child is always in the very center of the maelstrom of his own making.

Sometimes these take the form of "paracosms," imaginary worlds replete with systems of economy and governance.

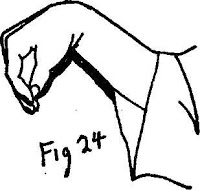

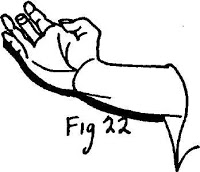

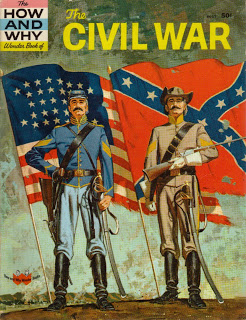

I do not remember having imaginary playmates; I was too desirous of real ones. Oh, the yearning for friends, fast and yearning in return to be with us, only us. But I did live inside places that fairly quivered with passion--that was where I belonged, oh boy! Blood and cries, cannonballs and bandages, horses wheeling and tattered banners whipped by the fury. Every moment a moment that tested one. I wanted to be tested. And, in my imagination, always to pass. (I was not the one with the skirts flying, by the way; I was the dirt-smeared soldier, falling to rise again and face the minie balls.)

At another point--or perhaps the same one, since that is the way it works when you're very young, no limits to simultaneity--I was utterly convinced I would one day live in the Newport mansion The Breakers. This constituted not just heroism, but heroic levels of wealth, so long as robber-baronial tendencies could be allowed in the truer world of the dream (they could). This may have coincided with the period in which I knew I would become an astronaut, visiting the moon on my way to farther reaches of the universe; this small imagining came courtesy of not just watching Lost in Space but inhabiting it. My first visit to a planetarium drove the belief deeper into the wild subconscious, where at will I could feel the loneliness hurtling by my rocketship at vast speed. How many lives did I imagine I had, in order to follow these disparate lines of work? Perhaps I would arrive home from a journey to Pluto and drop my bags in the marble hall of The Breakers, I don't know. Nothing made sense in that way, but it did make certainty.

That was it: certainty. There was a heightened sensation in these fantasies that I do not believe I could conjure today, even with drugs. I now live in a pastel world, reasoned and reasoning, with clean bathrooms. Every now and then, I mean.

Now that I am all grown up--too grown up, a very hard place especially for a woman, walking this bridge from the desirable to the . . . what? I don't know what to be, and that is the problem--does it mean I have figured it out? The theory supplanted by the pale real, no need for further questing. No more inhabiting the great hero of the mind's imagining. No living there, in the thrill of what I might call Deep Imagination. The place that echoes with cries and blurs with color, brilliant red and blue and hard grays. At least I can view it afar: through the window when he is out there, learning who he is among the trees that hide opponents, the ones to vanquish, always and soundly, vanquish.